When we say, “To learn, we must get out of our comfort zone,” we owe it to the seminal Russian psychologist Lev Semyonovich Vygotsky, who didn’t get much credit for his work during his lifetime.

Vygotsky profoundly influenced educational thought. His name is well known to most teachers, and his work has been the basis of modern evidence-based education research.

What are Vygotsky’s learning theories and contributions?

Vygotsky is known for several concepts in psychology and education, four of which are discussed in more detail in this article:

- Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): the area of understanding that lies just outside what one knows but is capable of learning.

- More Knowledgeable Other (MKO): an individual or entity with a higher level of knowledge, understanding, or ability in a specific task, process, or concept compared to the learner (a teacher, parent, peer, mentor, or even a tutor in digital form).

- Scaffolding: a process through which an MKO aids a student in their ZPD as necessary and tapers off this aid as the student gains confidence.

- Social Development: Vygotsky believed social learning precedes individual development and is unique to the individual; in other words, students move from “thinking out loud” through social interaction to using inner speech to learn.

Who was Vygotsky?

Vygotsky’s influence in the field of developmental psychology is extraordinary, given that he only lived till the age of 37, a relatively brief life cut short by tuberculosis.

Born in 1896 to a middle-class Jewish family in Orsha, a city in pre-revolutionary Russia (now part of Belarus), Vygotsky demonstrated intellectual aptitude from a young age.

His formal education included being homeschooled, attending a Jewish school, and later being admitted to Moscow University under an unfair “Jewish Lottery” system that ensured not more than three percent of the admitted students were Jewish.

In 1917, Vygotsky earned a law degree at Moscow State University, where he studied sociology, linguistics, psychology, and philosophy.

His intellectual interests at the time were wide-ranging; however, in his late 20s, he focused his academic work on psychology, completing a dissertation in 1925 on the psychology of art (a typically interdisciplinary topic for a thinker of such wide and varied interests).

In the same year, he received a degree in psychology in absentia due to a dramatic recurrence of tuberculosis that nearly claimed his life.

Although he recovered from this episode, the disease would ultimately take his life less than a decade later, in 1934.

Vygotsky’s key contributions

Vygotsky was a prolific writer who published six books in ten years. His interests were diverse but often centered on child development, education, the psychology of art, and language development.

He developed several important theories about how children learn and grow within culture and society.

Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development theory, in a way, criticizes psychometric testing, which only measures current abilities and not potential for development.

ZPD is “the distance between the actual developmental level as determined by independent problem solving and the level of potential development as determined through problem-solving under adult guidance or in collaboration with more capable peers.”

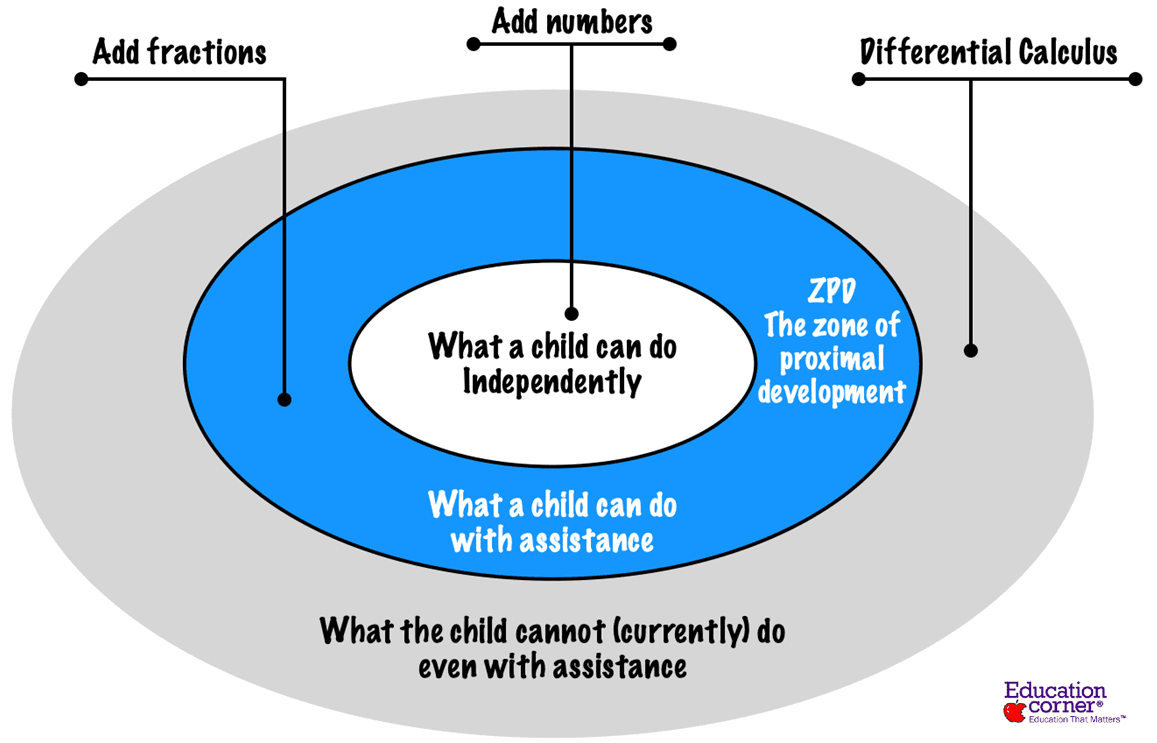

Lev Vygotsky’s Zone Of Proximity Development explained with a simple math example.

Vygotsky believed when a student is in the ZPD, providing appropriate assistance gives the student a “boost” to complete that task and, eventually, the ability to perform or learn independently.

In the above illustration, the white zone represents a child’s current understanding. Within its boundary, the child can learn through their own efforts.

The blue zone represents concepts a child can understand but with intervention and assistance. Grey is beyond their current ability to understand, even with assistance.

For example, consider a scenario where a teacher teaches fractions to students already familiar with simple addition. One student understands the concept of fractions but struggles to add them. This means adding fractions is within the student’s ZPD.

If the teacher guides the student through the process of addition by modeling the steps, asking leading questions, and providing examples, the student will eventually be able to add fractions without guidance.

However, if the teacher were to attempt to teach differential calculus, which requires far more math knowledge, it probably would not work. This is the grey zone.

A key ramification of this concept is that learning is not based solely on the development of a child’s cognitive abilities prior to learning. Rather, the learning process itself fosters cognitive development.

In the above example, learning simple addition led to the ability to add fractions, which (in the future) will lead to the ability to understand differential calculus.

This leads to Lev Vygotsky’s next concept, MKO.

More Knowledgeable Other

The idea of MKO goes hand-in-hand with the concept of ZPD. As the term suggests, MKO is someone who has a higher level of knowledge than the learner and is able to provide them with instruction during their learning process.

MKO refers to someone with a better understanding or a higher ability level in a particular task, process, or concept than the learner.

The most obvious examples of MKOs are parents and teachers. However, MKOs need not be limited to them, nor do they have to be adults. Peers can also be MKOs if they have a stronger command of the concept than the learning child.

An MKO serves as the means by which a child learns and understands concepts beyond what they might be able to grasp if left to their own devices.

Vygotsky tells us that cognitive development takes place during this learning process and not prior to the learning itself. This means the ability to learn a concept is developed simultaneously with the learning rather than one after the other.

The ability to learn a concept is developed simultaneously with the learning rather than one after the other.

Thus, MKO is the primary way for children to stretch their understanding beyond their current abilities through guidance and feedback. Both ZPD and MKO can, retrospectively, be seen as metacognitive strategies.

Scaffolding

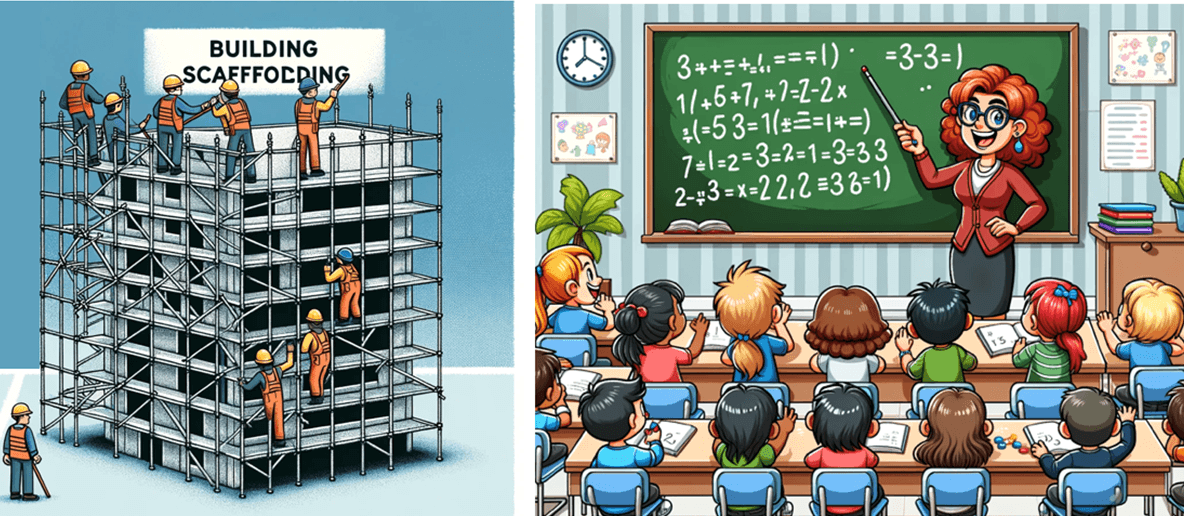

Scaffolding is a part of the ZPD theory and refers to the activities performed by an MKO to aid the learning process.

Scaffolding supports the student as they move through their zone of proximal development and eventually develop an independent learning ability. The level of support is gradually reduced as the student becomes more competent and confident.

Scaffolding in teaching is analogous to how scaffolding in a building is gradually removed as the construction progresses and the structure develops strength to withstand the loads.

Vygotskian scaffolding is also an integral part of Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction.

Learn more about scaffolding techniques in this dedicated article.

Vygotsky On Social Development

Vygotsky believed cultural and social factors influence cognitive development. He emphasized the role of social interaction in the development of mental abilities in children.

According to him, cognitive development is a socially mediated process in which children acquire cultural values, beliefs, and problem-solving strategies through collaborative dialogues with more knowledgeable members of society.

Vygotsky on Language and its role in the Thought process

Perhaps Vygotsky’s most dramatic and far-ranging ideas centered around the role of language in the process of thought and consciousness.

Highlighting the importance of language in cognitive development, Vygotsky felt that inner speech is used for mental reasoning, and external speech is used to converse with others.

Since these occur separately, before children employ words socially, they possess no internal language. A child learns external language (spoken and, eventually, written) at a young age and eventually internalizes and creates the mental landscape of consciousness.

Before children employ words socially, they possess no internal language. A child learns external language at a young age and eventually internalizes and creates the mental landscape of consciousness.

During the early stages, children literally “think out loud,” using spoken language to grasp concepts and reason through them.

As they grow, this increasingly becomes an internal process (“inner speech”), ultimately leading to cognitive processes, which are dependent upon language but no longer resemble the external language of spoken and written words.

Hence, according to Vygotsky, thought (including consciousness in its narrower sense of full self-awareness) was ultimately created socially as a product of linguistic development.

Thought, including consciousness in its narrower sense of full self-awareness, is ultimately created socially.

Vygotsky on Individual and Society

Unpacking the consequences of these ideas reveals how Vygotsky arrived at his view of the individual/social relationship.

For him, an individual was neither a self-contained agent navigating the social world nor a bundle of embodied responses to stimuli around them created through society. Vygotsky believed that individuals and society existed in an interactive relationship where each affected the other.

Individuals and society exist in an interactive relationship where each affects the other.

Society profoundly affects individual development, making it difficult to identify universal patterns. The individual, too, is not a passive participant but can (to greater or lesser degrees) influence the social environment around them.

Vygotsky claimed that infants are born with the essential abilities for intellectual development called “elementary mental functions,” which develop during the first two years of life due to direct societal contact. This includes attention, sensation, perception, and memory.

Eventually, through interaction within the sociocultural environment, these are developed into more sophisticated and effective mental processes, or “higher mental functions.”

Hence, depending on the quality of the sociocultural environment, a child’s mental abilities can vary.

Each culture provides its children with tools of intellectual adaptation that allow them to use essential mental functions to varying degrees of effectiveness.

For instance, while biological factors may limit young children’s memory, culture determines the type of memory strategy they develop.

In modern cultures, a child might learn note-taking to aid memory, but in pre-literate societies, a child might tie knots in a string to remember or carry pebbles to count.

Who Influenced Vygotsky?

Baruch Spinoza

Of the great thinkers of the past who exerted the most influence on Vygotsky, Baruch Spinoza, the seventeenth-century Dutch philosopher, is among the foremost.

Vygotsky was deeply interested in Spinoza’s thoughts and work. In his youth, he even conceived and began a major work on Spinoza but never completed it.

Spinoza’s mode of thinking appealed to Vygotsky for two reasons:

First and foremost, Spinoza, along with Descartes and Liebnitz, is categorized as a father of modern rational and scientific thinking, values that were central to Vygotsky.

Second, Spinoza’s theory of the world allowed for change and dynamic development, a gradual discovery of the unknown and its integration into the scheme of the known universe. This appealed to Vygotsky, who noted, “Without development, there is no history, no significance, no meaning.”

Vygotsky aimed to create a unified psychological science that integrated mental phenomena within a causal deterministic theory, influenced by Spinoza’s philosophical solution to the problem of dualism, particularly concerning emotions.

Karl Marx

Vygotsky was also influenced by the philosophy of Karl Marx, whose focus on the connections between the material world and human thought was highly influential to Vygotsky, particularly early in his career.

Vygotsky’s emphasis on the importance of social interaction in cognitive development aligns with Marxist principles of social relations shaping human cognition and behavior.

Additionally, Sigmund Freud and Ivan Pavlov’s ideas set the stage for Vygotsky. While also contemporaries, these two thinkers were significantly older than Vygotsky.

Sigmund Freud

Vygotsky acknowledged Freud’s pioneering work on the functioning of the mind, particularly the roots of psychoanalysis, which laid the theoretical groundwork for understanding mental processes.

Freud’s emphasis on the importance of childhood experience in creating the personality and the role of emotion in consciousness anticipated Vygotsky’s focus on childhood development and the place of feelings in cognition.

Ivan Pavlov

Pavlov’s interest in the interplay between external symbols and internal states of mind can be linked to Vygotsky’s notions of the social role of language in the creation of consciousness.

More importantly, Pavlov’s interest in applying psychological insights to learning theory closely mirrors Vygotsky’s.

Vygotsky’s theory of cognitive development, where he emphasizes the role of social interaction and cultural context in shaping cognitive processes, aligns with Pavlov’s focus on the interaction between the environment and the individual.

Vygotsky’s Contemporaries

Vygotsky’s brief life overlapped with notable psychologists such as Freud, Pavlov, William James, John Dewey, Wolfgang Kohler, and B.F. Skinner.

However, Vygotsky’s most notable contemporary was Jean Piaget, whose name is synonymous with cognitive development.

Piaget vs Vygotsky

Piaget and Vygotsky belonged to the same generation of psychologists and shared similar interests.

However, they shared contrasting perspectives on the learning process and the role of social interaction, language, readiness, and cultural influences in cognitive development.

Here is a quick comparison of their contrasting views:

| Aspect | Piaget’s Perspective | Vygotsky’s Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| The learning process | Conceptualized learning through a stage based model of development defined by one’s age. Believed that learning happens in distant stages based on development of brain. | Believed that learning happens best when its within one’s zone of proximal development and that age was less important. |

| Role of social interaction in learning | Saw children as solitary learners who learned through interaction with the environment. Believed development is largely fuelled from within. | Believed that socialization leads to learning and that society played a stronger role. |

| Importance of Language | Cognitive development stimulates language development. | Language development also stimulates cognitive development. The role of language in cognitive development was central to Vygotsky. |

| Concept of readiness | Children learn when they are developmentally ready. | Children learn through stimulation by parents / teachers and other environmental factors. ZPD is more important than age. |

| Role of cultural influences | Believed that development stages are universal among all children. | Cultural and social influences affect development. Children in different culture develop at different rates. |

| On Individual and Collaboration | Children learn best through independent exploration and discovery. | Children learn best in social situations and when guided by adults. |

While Piaget’s theories had relatively little to say about the role of language in cognitive development, Vygotsky considered it absolutely central.

Like Vygotsky, Piaget made significant contributions that influenced educational practices in various ways.

Find out more about Piaget’s learning theories.

Vygotsky’s Legacy

Today, Vygotsky’s theories range from being applied and celebrated across multiple contexts to being considered outdated.

His theories have transcended time and geographical boundaries and have been widely applied in diverse fields of inquiry, ranging from psychology to language education.

However, Vygotsky received little credit during his lifetime, and his influence remained fairly minimal for the first several decades after his death.

While Vygotsky’s work was known beyond his homeland, he wasn’t very influential beyond a small circle of followers in the U.S.S.R. His ideas fell out with Soviet thinkers, who were often critical of them.

Crucially, Vygotsky’s early death left many important aspects of his work unfinished, and few Russian translations were available beyond the U.S.S.R.

Despite this, his work gradually gained traction in the late 1970s and 80s. In particular, his ideas influenced a number of thinkers in the field of classroom learning.

Kieran Egan’s Cognitive Tools Theory, for example, was influenced by Vygotsky’s work.

But this has not been without some questions.

The unfinished nature of Vygotsky’s later work led to many “Vygotskian” concepts having a questionable connection to his original writings. This led to liberal, and at times fanciful, interpretations of his ideas being grouped under the label of “Vygotsky Studies.”

Even though Vygotsky may not have explicitly expressed all of the ideas that have surfaced since his passing and are now linked with his name, his research has undoubtedly acted as a driving force for deeper exploration of childhood development and learning.

Educational Applications of Vygotsky’s Work

Vygotsky’s ideas have become increasingly important in the field of education in the last few decades and have influenced many areas.

ZPD, MKO, and Scaffolding

Given the centrality of the “More Knowledgeable Other,” Vygotsky’s concepts have placed particular importance on the role of the teacher as a catalyst not only in learning but also in cognitive development.

A concrete example of Vygotskian influence is the concept of scaffolding, in which a learner first learns concepts and skills with external help that enables them to reach a second, higher tier of concepts until finally mastery of the overall skill or idea is attained.

Through this process, learners progress through the ZPD, learning not only the content but also how to learn about it, enabling them to reach higher levels of understanding.

Role of peers

Another specific application is peer-to-peer learning. As noted earlier, an “MKO” need not be an adult teacher. Peers who have a greater command of a topic or more developed skills can serve as MKOs, helping classmates gain greater mastery.

Ideally, peer-to-peer learning involves groups in which each individual can be an “MKO” on some aspect of the concept or skill, with each contributing in some way to the learning of their peers.

One offshoot of the importance of peers in development is the significance of play in the classroom, including (but not limited to) educational games.

Vygotsky suggested that play is an inherently beneficial activity independent of any specific concepts learned. Incorporating games–even those purely for entertainment and social interaction–has roots in Vygotsky’s work.

Role of language

Lastly, the centrality of language learning in the classroom across all subjects–not just those typically associated with verbal skills–is a legacy of Vygotsky.

Classroom techniques that ask students to describe or explain their thinking as a means of assessing understanding and building cognitive skills that will be important in future learning are Vygotskian in their assumptions.