Understanding Metacognition is essential for teachers guiding their students to a deeper understanding of the topics taught and their own understanding of how they learn, but what is it and how does it work?

What is Metacognition? Metacognition pertains to a student’s ability to self-critique their approach to a task and adapt their thinking to improve their understanding. The metacognition cycle guides students to improve the way they learn; 1. Assess the task. 2. Evaluate strengths and weaknesses. 3. Plan the approach. 4. Apply strategies. 5. Reflect.

What is Metacognition?

How often do you reflect on your own thoughts and behaviors?

As a colleague of mine recently put it to a group of assembled teachers:

Think about how you got here today.

Have you been here before?

How did you choose which way to get here – method, route etc?

Metacognition is often simply referred to as thinking about your thinking.

Teaching metacognitive strategies to students improves their higher-order thinking and increases their ability to make maximum progress.

Effective teaching is the best way to improve outcomes, especially for disadvantaged students.

The best teachers need a working knowledge and understanding of the most effective strategies in order to maximize the efficiency of their classrooms and the quality of the teaching and learning interactions therein.

By the end of this article, you may feel that you are “the converted” and you have been preached at; hopefully, no conversion is necessary if we all want to be effective teachers!

A lot of strategies that are now huddled under the umbrella of Metacognition and Self-Regulation are the same strategies many effective teachers have been employing, possibly in different guises or without conscious awareness in their classrooms for many years.

What Is the Research Behind Metacognition?

The term metacognition has been used to describe our own understanding of how we perceive, remember, think, and act, that is, what we know about what we know. (Metacognition: Knowing about Knowing edited by Janet Metcalfe and Arthur P. Shimamura (1994)).

Thinking About Thinking

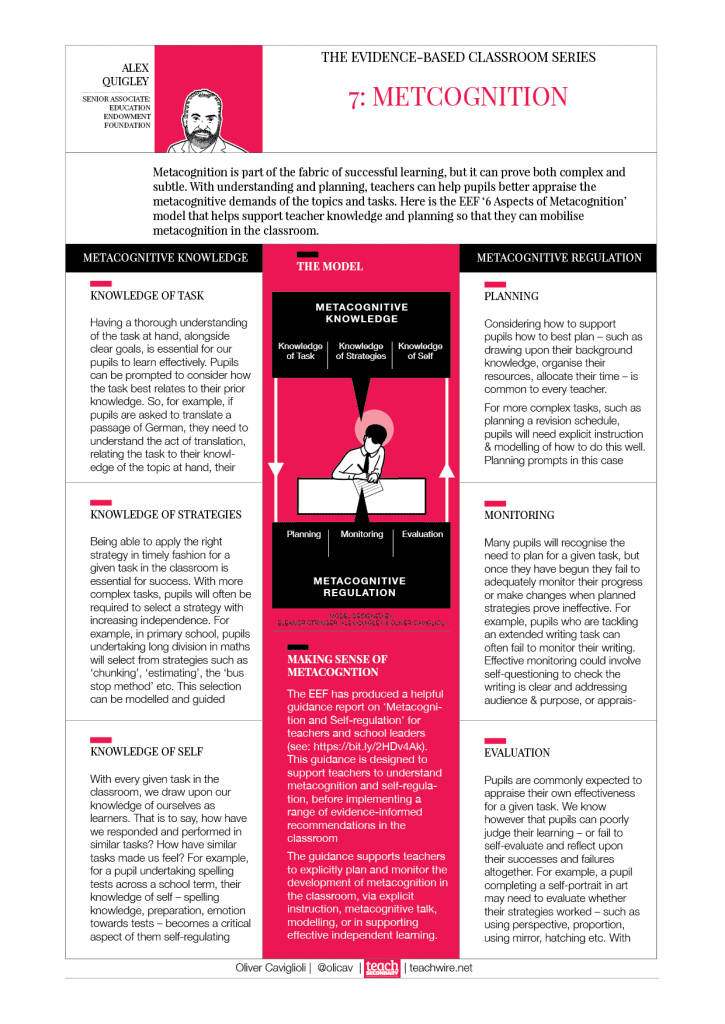

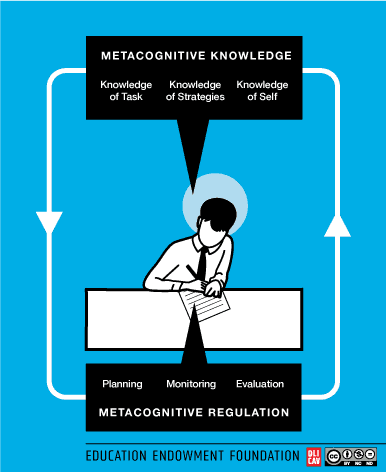

Metacognitive knowledge is the knowledge of yourself as a learner – how you learn best; the strategies you have at your disposal; the tasks you have to complete and how you complete them.

Metacognitive strategies help us plan, monitor, and evaluate our learning.

Metacognition as a concept is nothing new, the term itself was first coined in the 1970s by John Flavell. Over the years there has been much debate around the precise definition and the component parts.

Piaget’s Influence

In 1963, Flavell was the first to publish in English a study on the research and work of Piaget (The Developmental Psychology of Jean Piaget), from this, the science of cognitive development was born.

Looking back with the perspective we now have; the work of Lev Vygotsky on his Zone of Proximal Development, specifically the transition from a learner being directed by a “more knowledgeable other” to the learner becoming capable of understanding their own cognitive abilities would be considered metacognitive development.

Essentially, Metacognition is the ability we have to use our existing knowledge to plan strategies for approaching tasks, take necessary steps to problem solve, reflect on and evaluate results, and modify our approaches as required.

In an excellent article in the most recent copy of Impact Magazine for the CCT James Mannion defines it as ‘monitoring and controlling your thought processes’.

Mannion also urges us to be careful around the over-simplification of the concept; however, we can distil the basics.

Metacognitive Strategies in Education

Metacognition is one of the aspects students need in order to become self-regulated learners; it is important to remember that developing the former does not automatically create the latter.

Before setting off on anything classroom-based that you call a ‘metacognitive strategy’ you must have a basic grasp of the ways students develop their own metacognitive skills as a learner, and you must model these in your own practice.

Don’t fall into the trap of designing generic or explicit ‘metacognition’ lessons or ‘Study Skills’ sequences.

Embed the concepts more deeply in your subject-specific practice and focus on wanting the students to be more effective independent learners, reflecting on their approaches and regulating their behavior appropriately to ensure maximum success and optimized outcomes.

Why Is Metacognition Important?

One of the key conclusions drawn by the National Academy of Sciences in their “How People Learn II” report from 2018 is that:

“Successful learning requires coordination of multiple cognitive processes that involve different networks in the brain. In order to coordinate these processes, an individual needs to be able to monitor and regulate his own learning. The ability to monitor and regulate learning changes over the life span and can be improved through interventions”.

The EEF Guidance Report tells us that evidence and research suggest 7 months+ of progress “when used well” and that there is a lot of potential, “particularly for disadvantaged students”.

“When used well” is key, as is “potential”; we need to ensure that strategies and interventions designed to promote metacognitive awareness in students are supported by professional development for teachers.

Teachers should be guided in how best to embed these strategies into their classroom environments and day-to-day teaching and learning interactions.

These ideas around appropriate implementation are explored Joke vanVelzenin in “Metacognitive Learning; Advancing Learning by Developing General Knowledge of the Learning Process“.

“In today’s schools, most students are taught how to summarize, take notes, and read for understanding, though mostly without specifically being taught how to figure out by themselves when and why these learning techniques can be most effective.

Without obtaining a thorough understanding of the reasons behind the effectiveness of learning techniques, in that general knowledge of the learning process is being developed, learning can be hindered and become unnecessarily difficult, particularly, where new and unfamiliar learning tasks are concerned.

This makes the development of general knowledge of the learning process essential for lifelong learning.”

Metacognition in the Classroom

The EEF report is keen to point out to us that much less is known about effective implementation of metacognitive strategies in the classroom.

However, we can group together a range of approaches and opportunities that relate well to encouraging students to develop their metacognitive awareness.

One area where we can have immediate success is in the creation and management of appropriate resources. Encouraging students to use them effectively, thoughtfully and productively; this latter phrase encapsulates the metacognitive approach nicely.

So, what can we try?

Retrieval Practice

When done well and used appropriately retrieval practices help activate prior knowledge, ascertain prior knowledge and also give students practice at using previously learnt material effectively.

Thus speeding up the cognitive transfer from long-term to working memory and therefore embedding the learning more deeply.

Problem Solving

Worked examples and problem pairs are just a couple of examples of how modelling and articulating the process of using knowledge helps students better understand how to apply the range of metacognitive strategies.

We can also, as teachers make sure that we use questions to allow students to develop their reasoning and explain their answers. We can stimulate debate, press for depth and ‘design better conversations’ for learning.

Backwards Fading and Progressive Modelling

Both of these strategies can help students to the correct process by holding their hand through it in the first instance then gradually removing the level of support until the process becomes more natural and ‘automatic’.

Does this remind you of anyone?

Vygotsky perhaps!

If we adopt Rosenshine’s suggestions around introducing new material in small steps we ensure that we do not overload student working memory and we, therefore, do not hinder performance.

The end goal as a teacher is to fade ourselves and the resources away at an appropriate speed until students reach the level of performance that allows for proper independence.

This cannot and should not be done too quickly!

As well as the tools required to complete the task we can (and should) also teach the management of the task and which strategies are most effective in which situations.

In order to further the support that moves students towards independent and ‘self-regulated’ learning, we should ensure that we are designing those appropriate resources.

Resources that are streamlined, efficient and uncomplicated; ones that show an understanding of cognitive load and student working memory.

7 Examples of Metacognitive Questions Students Should ask Themselves

- What should I do first?

- Is something confusing me?

- Could I explain this to someone else?

- Do I need help to understand this?

- Where did I go wrong?

- Does this relate to other situations or prior knowledge?

- How can I do it better?

Metacognition Strategies

We can try getting students to reflect and evaluate their own learning experiences more with simple prompts:

-What concepts from today’s class did you find difficult to understand?

-Specifically, what will you do to improve your understanding of the concepts that were difficult?

We can also support students with their resource management. We can give them a range of well-taught and modeled study strategies that they can choose from when revising, for example; flashcards, MCQs, elaboration, self-quizzing and concept maps.

Giving them a well-structured study guide, they can work on what strategies work best for them.

Metacognition in action!

We can then ask them to articulate the success (or not) of their independent study to help them identify those strategies that are working and those that are not.

By setting goals and monitoring progress towards them, students become more aware of their own thinking and learning.

Perkins’ four levels of Metacognitive Learner (1992) can be a really useful template for not only identifying the different needs of students but also then enabling more focused and targeted intervention and support.

The Metacognition Cycle

- Assess the task.

- Evaluate strengths and weaknesses.

- Plan the approach.

- Apply strategies.

- Reflect.

Metacognition in CPD (Continuing Professional Development)

As mentioned earlier, institutions themselves need to recognize the potential of appropriately designed interventions to support metacognition.

In my view, this starts at the top and with the teachers themselves.

Focused, evidence-informed professional learning opportunities that are iterative and delivered by those with the appropriate knowledge, supported by frameworks and discussion models that help coach and develop staff delivery.

Simply ascribing a school’s ‘metacognitive approach’ to the creation of a one-off generic Study Skills program will not be effective.

The approach needs to be outward-facing and collegiate, with staff collaborating on the delivery of strategy as well as assessing its impact, perhaps in small focused Learning Groups.

When embarking on any form of action research in this way it will be key to ensure that the parameters are clear and precise and that there is a concrete idea of what ‘success’ looks like i.e. how its impact can be measured otherwise.

As with all CPD, be aware of the needs of those in the room and their own skills. How ‘novice’ are they? What support do they need? If teachers can develop and improve their own metacognition then they are better equipped to help develop it in others.

We need to distil the complexity of metacognition into steps that students and teachers can understand; as novice learners, we are initially poor in making judgements about our own learning, and as with anything our expertise increases over time and through experience.

Conclusion

If we want students to be able to become truly independent learners and to be able to think for themselves, we must teach them to think in a metacognitive way.

We don’t need to make huge changes to what we do, just tweak our teaching to set them up with the self-reflective questioning techniques.

What are your thoughts on metacognition in education? Comment below and let me know.