Whether you are remote teaching or teaching in your classroom, motivation is hard to instil in students. We can get students engaged easy enough but how do we motivate them to be better learners and achieve their potential?

In this article, we are going to look at why motivation matters to students, not just in our own subjects but as a life skill that will prepare them for success in anything they decide to.

We will them look at deep look at 5 of the most useful motivation theories and how they can be applied in a classroom setting. We will then discuss some other motivational ideas that are super helpful to teachers and students.

We will cross-refer to some of the most important learning theories (including Rosenshine) that are changing teaching as we speak.

Finally I will leave you with some takeaways that you can easily implement in your teaching.

Are you motivated to learn? Let’s get cracking!

Why Does Motivation Matter in the Classroom?

Well, ultimately, in our classrooms, motivation is what we need; students who are motivated will care more, listen more, put in more effort and pay greater attention to what is going on.

Essentially, they will learn more and therefore make it far easier and more pleasurable to teach them.

Have a think – what makes you tick? Why do you do what you do?

When you have the chance to unwind, what do you choose to do? Possibly something that you find easy – because it is nice to feel good about yourself, and to feel successful.

Think about motivation; what motivates you? And, on the other side, what de-motivates you? Reflection is the best place to start, and empathy begins at home.

Motivation is hugely complex, and also very abstract.

The hardest aspect is taking the fact that motivation is a basic human attribute and tailoring your thinking to the domain-specific contexts of education; what works outside the classroom may not work within, and vice versa.

Recent findings show that student motivation in online learning is low, but knowing quite how to harness the different aspects that constitute ‘motivation’ is hard – for a start, is it internal (self-driven forces from within) or external (actual things done)?

Students will only be motivated to learn if they acknowledge the need to learn, believe they have the requisite skill set needed for learning and also recognize the importance of learning in their lives.

That’s not an easy state to find as a starting point!

The old mantra of ‘motivation breeds success’ is also found wanting; success first will stimulate the motivation to drive to further successes, surely?

Engagement Vs. Motivation

A key concept to understand is that motivation and engagement are not – and never will be – the same thing.

Engagement, to reference Professor Robert Coe from 2013, is a poor proxy for learning, as indeed is motivation itself. It is where the motivation leads the student and the outcomes it manifests that is the true indicator.

Engagement is simply how much a student appears to be ‘busy’, i.e. how attentive they are, how focused they are, how little they are looking out of the window or gazing at the seductive details on the classrooms displays.

Motivation is how much they want to succeed in that given moment, and in that topic, subject or lesson.

The two are very different – engagement can be short-term, momentary, fleeting; motivation is a longer-term experience, with a clear goal – success.

In short, don’t take the engagement of students as an indicator of how much they want to learn.

Motivation can be driven by both intrinsic (personal beliefs and attitudes) and extrinsic (external rewards, prompts and pressures) factors.

It is important to acknowledge the existence of both but not assume that one is ever the dominant; as with any application of theory into practice, there must be a large slice of common sense and context.

5 Theories of Motivation and How They Apply to the Classroom

Let’s start by looking at some of the foundational theories of motivation and their relevance to education.

1. Alderfer’s ERG Model

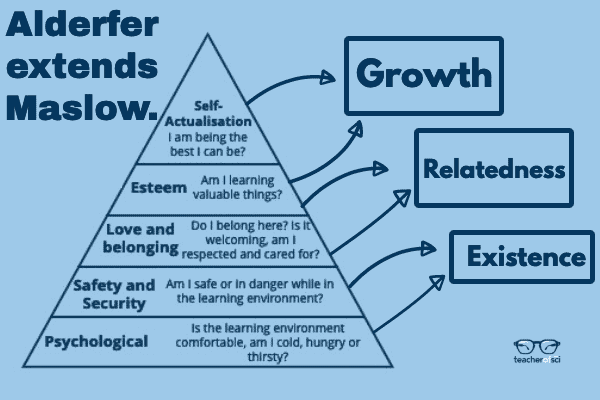

Clayton Alderfer (1972) argued that human motivation had three distinct categories; Existence, Relatedness and Growth, hence ERG.

Satisfaction drives progress from Existence, through Relatedness to Growth, and frustration fuels the return journey.

Note there are some similarities to Maslow’s model of hierarchical needs here in terms of stages, but Alderfer argues that all three of his areas can be addressed simultaneously and that sometimes regression can be powerful in order to facilitate personal growth.

- Existence is learner survival through basic needs being met, and therefore psychological.

- Relatedness is satisfaction achieved through good relationships in the classroom.

- Growth is where learners achieve satisfaction through attaining respect – personal development, essentially.

Alderfer’s ERG Model in the Classroom?

Meet the basic needs of your students on a psychological and physiological level, acknowledge their efforts as well as achievements and accept that in some cases regression to a lower level may be necessary to make better progress over the longer-term.

Alderfer promotes such things as ice-breakers and other simple games to encourage better classroom social relationships, so consider how that can be applied in both live and remote settings.

2. McClelland’s Needs Theory

David McClelland (1965) also argued that individuals have three basic needs that motivate them; achievement, power and/or affiliation.

This is a common ‘test’ in a lot of leadership development courses and qualifications, as people work out which one is their dominant trait!

Simply put, they are as follows:

- Achievement is the learner’s desire for recognition of work done well

- Power is the learner’s desire to be in charge.

- Affiliation is the learner’s desire for interaction and acceptance.

Notice how both McClelland and Alderfer look to the social relationships we have with others – a common theme in many motivation studies.

McClelland argues that one need may well be the dominant one but individuals may need to satisfy elements of the others to achieve a balance, a little bit like the ‘Humors’ of Elizabethan England.

McClelland’s Needs Theory in the Classroom?

Very simply, reassure those who make mistakes that they can and will bounce back; those who have Achievement as their dominant trait often suffer from fear of failure and need reassurance.

Although rare in a classroom setting, don’t let those who crave power undermine your authority; this links to management of classroom climate, accommodating individual needs and dealing effectively with poor behavior.

There is also a link here to your own motivation and efficacy as a teacher; if you feel scrutinized (Hawthorne Effect, perhaps?) or undermined then you too are compromised.

This also means that you must not let the desires of students to enhance their social relationships impact on their ability to learn in the classroom; striking that balance is hard – individual needs must be catered for…

3. Curzen’s Fourteen Points

Leslie Curzon’s work focuses on how in order to motivate we must involve; students need to be involved in the design of the learning program.

He took 14 points from a range of respectable sources and devised a ‘plan’, arguing that students’ attitudes to their learning are dictated by their inherent motivation, which in turn then determines how they approach their learning as well.

Some of the core aspects are:

- Understand student goals and motivations.

- Ensure goals are ‘goldilocks’ – not too hard, not too easy.

- Link short-term goals with longer-term outcomes.

- Present material enthusiastically (see Jang, below), clearly and in a meaningful way.

- Use frequent assessment opportunities to test understanding.

- Give regular and swift feedback.

- Acknowledge effort and achievement frequently.

Curzon in the Classroom?

In order to replicate some of Curzon’s ideas, consider the challenge level of tasks being set – the bar must be in the right place so as to give motivational value to the work.

A key requirement is that both you as the teacher and the students themselves know and understand what is expected and that you give feedback on effort as soon as possible after every test or assessment so that students know they need to learn from their mistakes.

4. Dweck’s Growth Mindset

Poor Carol Dweck; much of her ground-breaking and seminal work has been reduced to poorly synthesized ideas about simply telling students they’ll be fine if they think positively, and referring to multiple laminated posters on classroom walls.

At the heart of Dweck’s work is the idea that student motivation is based on their beliefs of their self-efficacy – two types of student (or people in general!) mindsets exist – fixed (intelligence is static) and growth (intelligence can be developed and improved).

Dweck points out that much of the growth mindset is intrinsic; students will not respond to interventions such as being convinced that their full potential will only be reached through constant learning and that challenge is welcome unless they themselves want the intervention to work.

This is where Dweck is often misunderstood, or not properly considered; growth mindset takes time to develop, to embed and must be fostered from an early age before too many aspects of self-doubt and lack of efficacy have time to manifest themselves.

Student mindset cannot be changed overnight!

Growth mindset in the classroom?

To develop a greater sense of growth in the mindset of students, consider how much you praise effort as well as results (in a similar way to Curzon’s ideas).

If praise is centred around the student themselves as opposed to their work then it implies that praise is an attribute of a fixed mindset.

Failure is down to lack of effort, not personal weakness; success comes from hard work!

Phrases such as ‘you tried really hard’ are far better than ‘you’re really good at this’ as the focus is on the effort, not a natural talent.

Students need to see through role-models, anecdotes and representations that hard work and effort lead to success, and challenge is an opportunity to improve.

5. Weiner’s Attribution Theory

In simple terms, Attribution theory refers to causes that individuals – in our case students – attribute to their own failures or successes.

Weiner (1985) looked at how these perceptions (keyword – perceived, not actual) affect the emotional and mental state of the student and then how this influenced motivation for future tasks.

Success breeds motivation, which breeds further success…

Weiner looked at factors contributing to success (or the lack thereof); students tend to attribute their academic success to either ability, effort, task difficulty or plain luck.

Weiner added his thoughts on how stable and controllable each of these factors were as follows:

An individual cannot control the difficulty of a test because it is an external factor that they can do nothing about; how much effort they put in is internal and entirely within their control.

Over-simplified perhaps, but hopefully easy to understand!

Weiner’s Attribution Theory in the classroom?

To start with, don’t over-praise or offer reward where it is not merited; as Weiner himself writes:

‘[a student] is not likely to experience pride in success, or feelings of competence, when receiving an ‘A’ from a teacher who gives only that grade’.

The important thing from the teacher’s perspective is that the perception of cause of performance is as important as the actual cause. Shift student thinking away from factors beyond their control and encourage focus on what it is within their remit to influence.

Encourage reflective questions and evaluation, especially with those who are most demotivated by repeated academic failure.

Exploring Motivation Further in the Classroom

At the heart of all teaching lies care for, interest in, and knowledge of students. What makes them tick, genuinely?

Stereotypes aren’t motivating; generic application of top-down theories provided by non-practitioners aren’t motivating; if you aren’t motivated as the teacher, what hope have you of motivating your students?

Indeed, to paraphrase many a better writer than I:

If you have no idea why you are doing what you are doing then you have no idea whether what you are doing means anything at all.

I need purpose. I need to see why I am doing what I am doing, and in particular what success looks like; clear goals, easily explained, with the appropriate steps in place to help me achieve it.

The same goes for our teaching and therefore our strategies for motivating our students – let them see, know and understand why they are doing what they are doing, with clear goals and outcomes for every step.

Reduce the cognitive load to make absorption of concepts easier, encourage retention through retrieval, practice until perfect… But yet, surely there needs to be some success?

Success will breed the motivation to foster future success, surely?

Yes; so make success an option in the classroom, nearly all of the time – just not every time.

Rosenshine suggests that an optimum success rate is 80%; keep it that way; like Tantalus, have certain things just out of reach but keep them as desirables.

Goals can be short, medium or long term, but I would argue that students need to be aware of them all, at the appropriate time.

We zoom out to zoom in:

- We help students orient themselves in their learning state and make them see the purpose of their endeavors.

- We provide concrete examples of abstract concepts.

- We foster the joy of academia.

- We praise success and effort. We challenge the accepted truths.

- We role-model the joy of learning.

Jang (2008), looked at how students who were told prior to a lesson what the rationale was against those who weren’t; by the end of the lesson those who knew its purpose were 25% more engaged and afterwards demonstrated over 10% higher levels of factual and conceptual understanding of the topics covered.

Yes, figures can be refuted but they mustn’t be ignored without reason – purpose held sway here.

To elaborate, in Jang’s study, the outcomes themselves weren’t the only driver; students were also told why and how the lesson would help, why it might be difficult and why it was worth sticking at it – students needed to see ‘the importance and personal utility within the task’ and to ‘perceive high autonomy while working on that task’.

I see a process of Show and Tell.

As a student, I can be told that it is possible to jump nearly 9m. I don’t believe it; this seems ridiculous, especially when that distance is physically measured out on the classroom floor (if we have such classroom sizes!).

- I am TOLD it is possible. It’s not true.

- Then I am SHOWN Mike Powell doing just that at the 1991 World Athletics Championships and Carl Lewis nearly doing it too.

- I can’t refute it, because I have just watched it happen. And I want to replicate it. And beat it.

- Because I know it can be done.

- And if someone older than me did it before me, why shouldn’t I be able to do it better?

Clunky analogy possibly, but it captures the heart of teaching – modelling.

Showing and representing success through stages, with plenty of checking for understanding, lots of low-stakes checks of skill, ensuring the foundations are in place but still pushing – much of motivation theory can be found in coaching approaches, and rightly so.

I must be sensitive to the needs, desires, goals and potential of my students.

We must be aware of the difference between actual learning and looking like learning; the latter is very easy but, as pointed out by many, and by Nuthall in his seminal work ‘The Hidden Lives of Learners’, engagement is a poor proxy for learning; looking busy is easy, learning is not so.

Carrot or Stick?

Beware the easy reward as the motivator – not so…

Carrots are fine, but they must be duly earned; look back at Weiner (above); a reward for no effort is no reward, and the future of that reward is diminished.

Rewards need reasons behind their award; this helps give tasks purpose.

There is nothing more demotivating for a ‘standard’ student who tries their very best to see a ‘troublesome’ student gain a reward for what for them is a basic expectation.

Don’t dilute in order to manage the classroom; focus on the discretionary effort, beyond the basics of the task – if you have pitched at a la Goldilocks (not too hot, not too cold, just right…) then you are creating climates where consistency is easy.

You can create success in your classroom by being active and attentive; plan for learning in small steps (Rosenshine); model outcomes and explain processes, tweak the direction of the lesson to accommodate the mood of the room.

M is for Motivate:

In his MARGE model, Shimamura tells us that, due to all the distractions in a classroom and the effort required to learn, it’s important to support students in generating mental motivation to focus on the content being studied.

He tells us that:

“There are times when personal interests make it easy for us to seek new information, such as learning about a favorite topic, activity, or hobby. The trick to motivation is to expand the spectrum of pleasure-seeking experiences and push ourselves into new learning situations”…

…Indeed, just enveloping ourselves in a new setting and breaking away from regular habits will fully engage our learning machine. Take a walk around unfamiliar terrain and you will motivate yourself to attend, relate, generate, and evaluate”…

Shimarura focuses on how teachers can create environments for students that then encourage them to attend, relate, generate and evaluate for greater learning – it’s a great read.

Shimamura’s main ideas translate easily to classrooms

- Stimulate curiosity. Frame learning through Big Questions and links to larger schema

- Harness the power of story-telling. What will happen next?

- Consider the ‘aesthetic question’. Engage emotional responses and personal views on topics

- Explore new places. Virtually if you have to!

Other Views on Motivation

One very useful strategy for improving motivation in the classroom (live or online) is the use of low-stakes testing and regular retrieval practice; students who experience more successes then feel more empowered and motivated to achieve more!

Much of motivation is also geographically contextual in its framing; it is widely recorded that East Asian students, teachers and parents are more likely to value effort and its role in achievement than the innate ability of the student themselves.

By having high expectations of our students and sculpting the work accordingly; teacher mindset and expectation are vital to lifting the lid on student success.

Rattan et al (2012) found that teacher mindset affected the way teachers communicate with students.

Students who heard words of feedback and instruction based around strategy were more likely to succeed in future assessments than students who heard comfort-focused works, which they associated with n assumption that they thought the teacher lacked faith in their ability.

Rosenthal’s work around teacher expectations and Pygmalion is worth investigating further too – a rising tide lifts all ships, and all that…

Martin et al (2008) considered what is called ‘Academic Buoyancy’.

5 ‘C’s of Confidence, Coordination, Commitment, Composure and Control that, when managed and fostered, enable students to overcome daily challenges by providing them with the strategies to more in charge of what they themselves can achieve, and boosting their self-efficacy and self-regulation.

Yet another sink or swim metaphor to go with our rising tide…

Questions You Could Ask Yourself

- To what extent are your pupils intrinsically motivated in your classroom?

- To what extent do you use rewards prudently in your classroom? Why? How do you know?

- Do you give praise that is sincere, emphasizes process and is immediate?

- Do your pupils feel supported and able to make mistakes?

Motivation in the Classroom Takeaways

- Help students believe that they can improve and can be better in class

- Focus on and model process as well as outcome

- Construct a climate where students (modeled by you) see mistakes as learning opportunities, not criticism

- Use the bigger picture to help students see how the here and now links to the future

- Explain failures and successes

- Control the controllables yourself as the teacher, and encourage students to do the same

- Allow for small successes to be factored in to ensure motivation is harnessed for further success down the line

- Believe in your students as individuals and their capacity for improvement and success

Ultimately, students are humans, and humans are social creatures; as a teacher, you must create a climate-informed by your own understanding – that fosters and supports learning.

References other than those embedded within the text:

Jang, H. (2008). Supporting students’ motivation, engagement, and learning during an uninteresting activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 798–811.